Poor Man's Sheep

0400 Hours. Somewhere in the vacant desert northeast of El Paso, TX.

Red and blue lights pierced the dust and pre-dawn darkness, violently flashing off the truck’s back window and rear view mirror. Adam rolled the gritty window down, allowing the cool, dry air to rush in. Immediately, all three of us were blinded by white LEDs, followed by an authoritative male voice forcing an unnaturally deep tone. "US Border Patrol! Stay in the vehicle."

If we could’ve seen anything other than the 2 million lumens emitted by his flashlight, we'd have gathered as much from the bold letters emblazoned across the front of his ballistic vest.

"License, registration, and state the nature of your business," demanded the short young man, as he peeked over the door of the lifted Chevy. What he meant to say was, "What in the %#€* are you three idiots doing in the middle of the desert at this time of night, on a known smuggling road, in an all-camouflage pickup with Montana plates."

"We're going aoudad hunting," Cody replied from the passenger seat with as much enthusiasm as he could muster. The agent's hand remained on his pistol as he shot us a distrustful glance. "Stay in the truck. I'll be right back."

Within minutes, two backup vehicles bounced into view, their huge light bars illuminating the cactus-strewn wasteland on either side of the gravel road. After a while, a senior officer came to the window.

"So you're Barbary sheep hunting, huh? Well good luck, here are your driver’s licenses. By the way, we call them The Poor Man's Sheep."

Strange Sheep

The animal got this nickname because it can be hunted for hundreds of dollars, instead of tens of thousands, which is often the going rate for the four curly-horned varieties of sheep native to North America. But despite the budget price tag, expect the physical and mental challenge to be on par with any Bighorn or Dall hunt.

A Barbary ewe

A Barbary sheep hunt begins much the way any other sheep hunt does. A lucky hunter learns that he's drawn a tag and proceeds - with much excitement - to call some friends to see who can go along. And that's how I found myself pulled over by border patrol near the Texas/New Mexico border this past February.

Cody's lucky sheep socks had come through for him again, but this time we were headed south, for Barbary sheep, not north for Dall sheep. And unlike the desert bighorn that's native to NM, this particular southern sheep has a comparatively short history in the US.

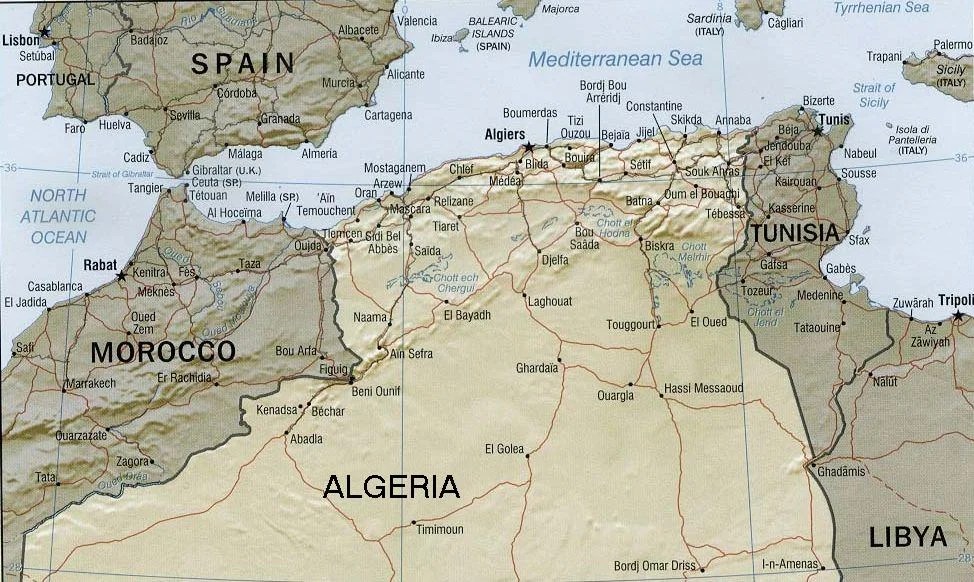

What’s referred to as the Barbary Coast, in northwest Africa, is a mountainous, arid, unforgiving swath of dirt that stretches along the southwestern Mediterranean Sea from Morocco to Libya.

The Barbary Coast of northern Africa

It’s a sandblasted part of the world that, to westerners, is known for little more than belly dancers and an unresponsive US Secretary of State - thank god not one in the same. Those things aside, the Barbary Coast also gives its name to a strange dark-horned member of the Ovis family, often called aoudad.

The Barbary sheep was first brought to the US in roughly 1900, and at the time was kept in zoos and reared on game preserves in the southwest. In 1950, the peculiar looking sheep was released into the wild in New Mexico, and again in Texas seven years later. The aoudad is now relatively well established throughout southern and central New Mexico, though there really aren't any densely populated areas.

When Cody asked if I wanted to join him on another sheep hunt, the answer was a quick "Yes." New Mexico unit 29-30 offers moderate altitude, steep, cliffy terrain, cacti and, apparently, confrontations with Border Patrol... Sounded smashing. This time, Adam Johnson was planning to come along too.

Adam is a fly fishing and hunting guide from Idaho who works for Cody, at Cody Carr’s Hunting Adventures. So that meant a trip with two of my favorite wilderness cohorts.

Cody Carr (L) and Adam Johnson.

Top Down Ram

Once border patrol turned us loose, we drove another half hour before shutting the truck down. We simply pulled off the dirt road as the earliest hints of violet sunrise graced the eastern horizon. Cody slept in the truck. Adam and I grabbed sleeping bags and passed out on the roof of the pop-up camper. We slept for about an hour before piling back into the truck and completing the drive to where we'd been told we might find a herd of aoudad.

Three individual mountains, each with a prominence of maybe 2,300 feet, broke the otherwise featureless terrain of scrub brush and water tanks. For a day and a half we picked the slopes apart with binoculars and spotting scopes finding neither hide nor hair of the dirt-colored Barbary sheep. We did find a dead coyote, and we learned that southern New Mexico can be a windy devil.

One of the mountains we glassed near the Texas border.

Time to move on. We headed toward another area within the same management unit. Instead of free-standing mountains, this area offered hunting on a "rim", where a high plateau dropped about 3,000 feet to a lower desert floor. This geological feature probably stretched 40 or 50 miles. Streams coming down had carved small canyons into the face, and it was up into these that one needs to explore to find the elusive sheep.

Up to this point we had hunted from the bottom up. So we decided to drive the 50 or so miles to the top of the rim in order to hunt from the top down. We split up without ever leaving earshot, walking the top of the rim and glassing down into the various crags and canyons.

Cody glassing from the top down.

Maybe half an hour passed before Adam jogged over and rounded us up. He'd found the first sheep of the trip; about half a dozen animals and what he thought was one ram.

Dropping carefully below the jagged rock crest of the rim, we settled in behind our glass to better judge the sheep. Immediately we realized that these animals are really hard to see. They blend right into their surroundings, and don't have a white rump patch like some big game. The profile of their curved horns, more than anything, gave their position away. At about 400 yards we saw what looked like a pair of rams lounging separate and below a group of ewes and lambs. It’s worth mentioning that both males and females have horns, so it's hard to tell a young ram from a ewe.

A PhoneScope shot (iPhone 6 and Vortex Razor HD 22-48 x65) shows the lower ram.

Having never judged these creatures before, we weren't positive that the bigger horns on the lower two animals meant they were rams. But before long, one sheep turned its back to us and confirmed it; The biggest in the bunch was definitely a ram.

The red dot marks the location of the sheep when Cody fired.

Cody took a prone position on an ideally-situated hoodoo and drew crosshairs on the sheep. As the first shot rang through the canyon, Adam and I watched the bullet strike the ram in the flank. It ran uphill 60 or 70 yards before Cody fired again. Again, the 300 Winchester struck about 6 or 7 MOA left of the shoulder, but this time the ram rolled, coming to a stop alongside a sun-bleached log.

It could be that the scope got a nasty bump along the trail, but the rifle is the same one that he used to take his Dall ram with surgical precision in 2016. Cody anchored the ram with a third shot, compensating for the errant windage.

A quick congratulations before we dropped further into the canyon, and we quickly realized why the sheep tuck themselves deep into the craggy drainages. Despite the warm sun, the wind howled up through the ravine, sandblasting everything it contacted. As we cut the animal up, getting meat into bags before it attracted dust was a challenge.

Success on a public land, DIY Barbary Sheep.

Aoudad have a mane on the brisket and legs. Their horns have a unique lateral wave present from tip to base, and their hooves are unbelievably soft considering the terrain they live in. Several times on the hunt, I was poked by cactus spines that fully penetrated my leather boots. And these are the same cacti that are consumed by the aoudad as a source of water in lieu of streams and ponds.

We packed the sheep out, broke camp, and headed north. There were a few days left and more sheep to kill.

A real sheep hunt

At about 60 miles an hour, Adam locked the truck brakes up. We felt a thump, and when we'd come to a screeching halt, a cloud of smoke rolled past the light bar. We jumped out to find a very large, very dead Javelina under the truck. Knowing it would be illegal to keep any part of the pig, we took a few photos in the middle of the road before dumping the carcass in the weeds. North we continued.

Adam and I with our trophy javelina.

The management unit we were headed to next offered Barbary sheep tags over-the-counter, with no closed season. Cody couldn't buy another, but for Adam and I, it was free game. We hit a Big Five Sporting Goods, spoke with two employees who knew less about New Mexico Game laws and licensing than we did, and Adam bought a tag. I held off, figuring that we had to notch a second tag before worrying about a third. Luckily we had a back-up rifle; a custom 7LRM that shoots lights out. We spent the first afternoon glassing unsuccessfully.

Adam behind a pair of 20x Kaibab binoculars.

That night, in a hotel, we cruised Google Earth looking for the nastiest canyon we could find. That proved difficult because all of the terrain was nasty. The rim we planned to hunt probably rose about 4,000 feet from the valley floor, with canyons stretching up and in for likely three miles. All of it was laced with impassable cliff bands.

Cody crosses below one of many cliff bands, which appear deceivingly small from miles away.

The next morning was cold. We were glassing from an access road at the bottom of the rim when I picked up some slight brown movement about two miles away. Once we put a spotting scope on that area, we realized that there were more than a dozen sheep making their way up the canyon. I think it shocked all of us considering that I'd seen it through a pair of 10x binos. Last year on the Dall sheep hunt, I took a pair of Leica Geovids. This time, to shave a little weight, I packed a pair of Vortex Razor HDs, and was at no optical disadvantage compared to using the Leicas.

Without wasting any time, we threw our packs together and covered the one mile of flat ground in no time. When we hit the base of the mountain, we realized that this was definitely uglier country than what unit 29-30 offered. We climbed the rock bands we could and skirted the ones we couldn't. It only took two handfuls of cactus spines before I learned not to put my hand down on the ground for support.

As we climbed, we only got one fleeting glimpse of the sheep. When they climb, they climb fast. They seem to run everywhere they go, whether or not they're being pressured. As we continued the stalk, we realized that we had headed up from the flat one canyon too early. The canyon we climbed and the one that held the sheep were separated by a smaller, hidden canyon.

Crossing the draw was brutal. It was steep and strewn with loose, noisy rock. At one point we got high enough that Adam could have taken a steep, 880 yard shot but he decided against it. The cliff bands that crowned the canyon formed a magnificent amphitheater.

Here, you can see the huge "Amphitheater". I'd guess it at 1,500 feet tall.

We climbed toward it, hoping to find a place that Adam could shoot less than 500 yards. As we approached the best looking ridge, we spooked a group of mule deer and blew them right into the big canyon. The wind wasn't dead wrong, but it wasn't good either. We figured that the amphitheater probably captured, swirled and held any scent that came even remotely close to the sheep.

Whether it was the deer, the scent or both, all the sheep - probably 30 or 40 in all - crested a high pass into an even bigger canyon and vanished like brown desert phantoms. Not five minutes passed before we heard a rifle report, or so we thought. But given the way sound traveled along the cliff walls, there was almost no telling which direction it came from. With little other option, we followed where we thought the sheep had gone, into another canyon.

But crossing the "amphitheater" canyon proved sporting. We had to circumnavigate one huge monolith in its center, side-hilling the bowl twice to reach the crest. Every step on loose scree threatened to give way and send you on a long, cactus covered slide. We picked up dead yucca stalks, which served as impressive, lightweight trekking poles.

At the top we were greeted by great views and little else. We spent a full melanoma-inducing hour glassing this new, four-mile deep canyon before attempting to climb off the mountain. We walked the ridge out hoping to find a place to drop straight down to the truck, some three miles below us. Despite what the topo maps showed, dropping straight off would have been a very literal process. Cliffed out, we had to retrace each step we'd taken to that point.

There simply wasn't a better way down.

At times, it looked as though either of the first two canyons offered more direct routes down, but we stayed our course and realized later, from different vantage points, that it was good we hadn't strayed. The dry creek bottoms that funnel out the canyons had various 20 or 30 foot sheer drops.

By the end of the day we probably covered 5 miles as the crow flies and 10 miles by foot. We arrived at the base of the mountain as the sun sank low. Montana and Wyoming were expecting a big snow storm within the next 72 hours, so we knew this night would be our last.

We sat at the foot of the mountain in a creek bed, sharing the last Powerade we had, watching dusk creep up on the desert. Rabbits ran from bush to bush and bands of javelinas moved nervously through the cacti.

Adam began digesting his tag sandwich with a smile. Cody commented that he hadn't been home to see his little girls in 7 weeks. I took pictures. Exhausted, sunburned, and happy, we all agreed that it was good to be sheep hunters. The Poor Man’s Sheep did not disappoint. You can watch the video, here, but don't forget to watch it in HD.

Give us a follow on Instagram (@TransientOutdoorsman) and Twitter (@TransientOutdrs). We’re on Facebook and YouTube, too!

# # #